The Amphibious Assault on Fort George – May 27, 1813

The Amphibious Assault on Fort George – May 27, 1813

(Niagara Historical Society and Museum)

An amphibious assault requires the rapid buildup of combat power ashore, from an initial zero capability to full coordinated striking power as the attack progresses toward AF objectives. In the amphibious assault, combat power is progressively phased ashore. The assault is the most difficult type of amphibious operation and one of the most difficult of all military operations due to its complexity.

- JOINT PUBLICATION 3-02, AMPHIBIOUS OPERATIONS, 18 JULY 2014

Because the Niagara River was an essential conduit for logistics and communications for both Britain and the fledgling United States, military actions on the Niagara Frontier dominated events of the War of 1812. Control of the Niagara River allowed for both the growth of the fledgling United States, and the continued presence of Great Britain in North America. The Niagara was the gateway from Lake Ontario and Lower Canada to Lake Erie, Upper Canada, and the Old Northwest Territory bordering the Great Lakes. After war broke out in June of 1812, battles at Queenston Heights, Fort George, Stoney Creek, Beaver Dams, Fort Erie, Chippawa, and Lundy’s Lane were all fought over control of the Niagara peninsula and river. However, one of these battles stands out as the first major amphibious attack executed by an American Army – Navy team. This was the Battle for Fort George.

Since the declaration of war in June of 1812, U.S. and British forces had been crossing the river in raids. One ill-fated, poorly executed attempt at conquest of Upper Canada occurred at the Battle for Queenston Heights in October of 1812. An initial U.S. success on the battlefield turned into a dominant victory for the British, their Canadian subjects, and their allies of the Six Nations.

In the fall of 1812, New York State Militia Major General Stephen van Rensselaer commanded an untrained, demoralized, and poorly supplied Army on the Niagara Frontier. He and New York State Governor Daniel D. Tomkins feared a British attack at Fort Niagara would result in its loss, and wanted to begin an offensive in Upper Canada before winter fell. Regular Army reinforcements, under Brigadier General Alexander Smyth refused to report to van Rensselaer, destroying any unity in command on the frontier. Aside from the normal antipathy held between militia and regulars, the heart of this dispute lay in the political struggle between Republicans and Federalists—politics would cast a shadow over U.S. unity during the entire war.

The Canadian river-town of Queenston was a busy landing on the western shore, at the foot of the Niagara Escarpment, where all British boat traffic loaded or offloaded, and portaged around the cataracts of Niagara Falls. Dominating the town were the heights of the escarpment immediately to the south, rising some one-hundred-eighty feet above the quick moving river. Van Rensselaer saw that control of Queenston would put British forces along the rest of the Niagara, and points west, at a disadvantage.

From the start, execution of the U.S. plan to cross the river from Lewiston to Queenston lurched and sputtered. Van Rensselaer had 4,000 troops, militia, and regulars at his disposal, but only 13 boats to shuttle them across the river. As each of the boats only carried three dozen, it would take hours to establish an overwhelming force on the opposite shore. Lacking a marshalling area before embarkation points, small unit commanders loaded boats as they saw fit, resulting in chaos on the landing near Lewiston.

Once the initial group of Americans made it across the river, they did succeed in taking the heights above Queenston, and captured British artillery pieces which dominated the approaches to the north, towards the garrison at Fort George. When British and Haudenosaunee reinforcements joined the battle, and the Americans began suffering casualties, militia members still in Lewiston balked at boarding boats to join the fight. Barracks lawyers amongst the militia members determined that they’d volunteered to defend New York, not invade Canada. The sound of gunfire, the smell of cordite and blood, and the pealing of Iroquois war-whoops, amplified by the sight of wounded comrades being transported back across the river, all proved to be too much for the militia.

One professional Army officer who’d just joined Smyth’s force, Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott, commanding a detachment of the Second U.S. Artillery, did volunteer to cross the river, without his guns, where he led a defensive action on the crown of the heights. In fierce fighting the Americans found themselves with their backs to the cliffs above the river. After hours of fighting, any Americans still surviving elected to surrender to the British, avoiding a total slaughter. The Battle of Queenston Heights has gone down in the annals of Canadian history for the heroism of the Canadian militia defending their home soil, and for the loss of the charismatic General Isaac Brock. American losses were 80-100 killed, 80 wounded, and 955 captured, including Winfield Scott. Canadian losses were 21 killed, 85 wounded, and 22 captured. [1]

The failure at Queenston has been laid at the feet of politicians posing as military leadership by the State Militia command; their failing to amass a force large enough to take and keep the crossing open, the reluctance of the militia to face the British and their Haudenosaunee allies; and in not having enough boats available to transport a force en masse across the swiftly flowing river. The British/Canadian victory reinforced their victory at Detroit and minimized U.S. sympathies amongst many Canadian settlers on the Niagara Peninsula.

After a recovery over the winter of 1812-1813, President James Madison identified taking Montreal essential to the defeat of the British. Commanding the Northern Army, Major General Henry Dearborn (a veteran of the Revolutionary War and formerly Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of War), felt he lacked the men, arms, and materiel to defeat the 12,000 British soldiers at Montreal, and shifted planning to taking Kingston at the eastern end of Lake Ontario. Conferring with local unit leaders and Commodore Isaac Chauncey, who commanded the U.S. Navy on the Great Lakes, Dearborn estimated he didn’t have the force to defeat the 8000 at Kingston either. So Dearborn shifted focus to York, Fort George, and Fort Erie—taking these points should assure U.S. control of the Great Lakes to the west, and would deny the British and their Six Nations allies on Lake Erie of both communications and supplies.

Dearborn picked two lake towns to fight the British in the spring of 1813; the provincial capital of York (Toronto) and Fort George (Newark, now Niagara on the Lake). The April 27th amphibious raid on York was intended to secure supplies, weapons, and the capture of a Royal Navy ship. Led by Brigadier General Zebulon Pike, Dearborn’s force of seventeen hundred easily pushed the British out of York, but suffered great losses when the retreating British ignited the main magazine at the fort—Pike was killed by falling debris from the explosion. Disgruntled Canadian citizens joined out-of-control American forces in looting York, and burning the parliament building. U.S. forces were unable to secure the Royal Navy’s HMS LADY PREVOST, as it had sailed four days before the attack. On May 8 the U.S. withdrew from York after suffering over three-hundred killed and wounded; the British suffered 200 killed and wounded, with 300 Canadian militia captured.

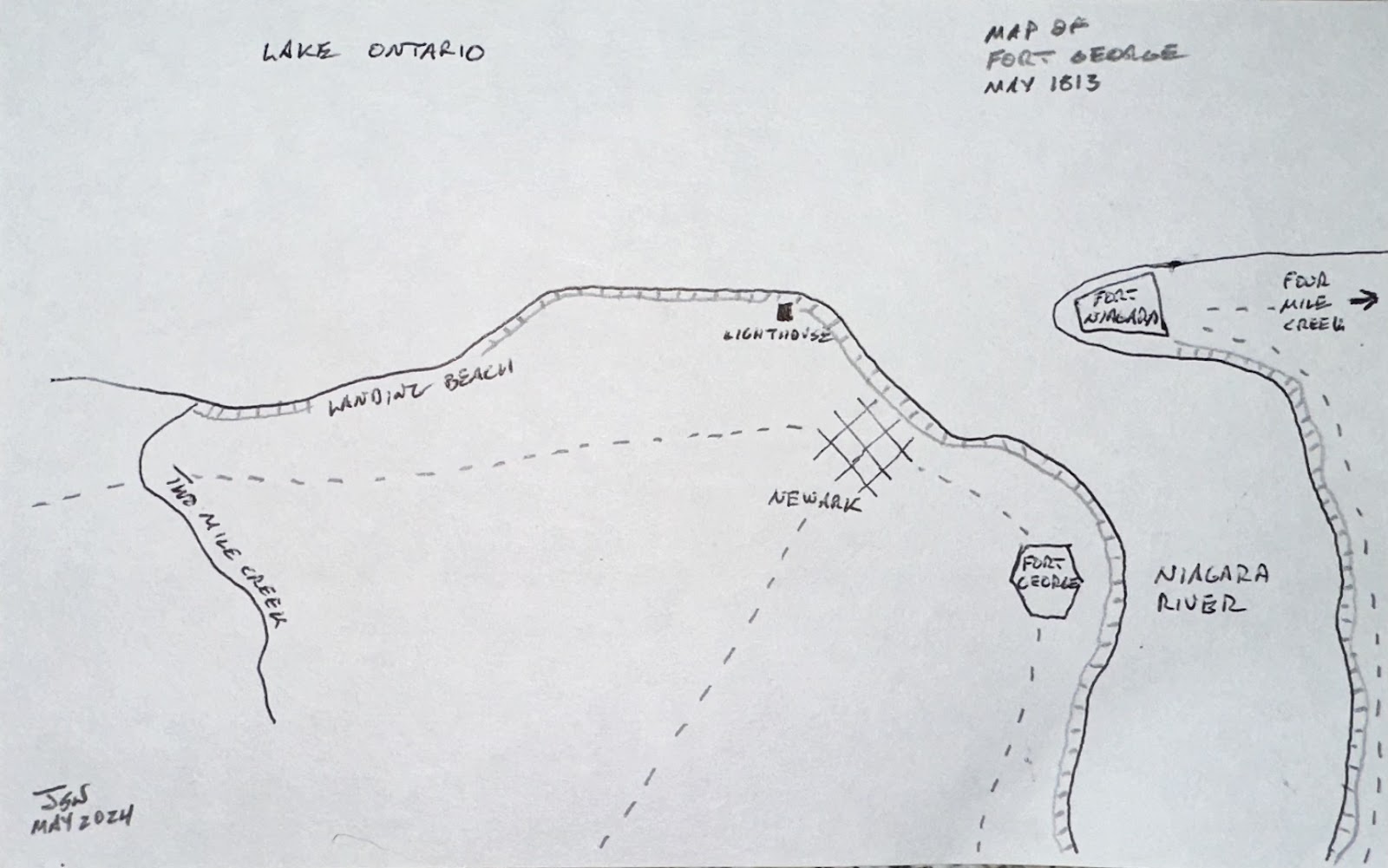

As the Navy returned Dearborn’s force to Fort Niagara, where many of the wounded were transported on to the hospital in Buffalo, he turned his focus on securing the Niagara River by taking Fort George. Secretary of War John Armstrong urged Dearborn to attack with overwhelming force, hoping to avoid the debacle of Queenston Heights. As a result, Commodore Chauncey’s Lake Ontario fleet shuttled troops from Oswego and Sackett’s Harbor (Watertown) to an assembly point just east of Fort Niagara, at the mouth of Four Mile Creek. Dearborn soon had three thousand men on hand at the Niagara, and had gained an experienced, professional officer to assist in planning the operation in early May, when Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott rejoined the Army after being paroled by the British. Designating Scott an Adjutant General, Dearborn turned over planning of the operation on Fort George, and Scott placed himself in command of the vanguard of the force.

Scott was now an experienced battle veteran who retained a penchant for studying the military writing and carried a personal library with him in his travels. Suspended from service in the army in 1810, Scott had spent the year studying classical military texts—concepts in these works would contribute to the volumes of U.S. Army doctrine and drill manuals he would develop over the rest of his career.[2]

And the importance of drill in this age cannot be overstated. Drill developed the means to move a mass of humanity efficiently from one point to another point, directly in contact with an enemy. Moving in column, or line, and executing flanking maneuvers, obliques, and actual rifle drill itself instill a discipline in a force that is essential when the cannons roar and bullets fly. The concept of drill itself raised a conceptual conflict between militia and regular forces on the U.S. side at the beginning of the war. American militia, lacking the exposure to rigorous drill periods, had an informal style of fighting, lacking in discipline. This style was not to be confused with highly trained regular units trained to fight in woods and villages as light infantry, or as skirmishers.[3]

Scott’s affinity for drill, personally schooling officers as they drilled their troops, and penchant for planning, would reap immediate rewards at Fort George, both ashore and in the shipboard movement. Scott had studied many of the available drill manuals, including those not in English. One French volume, translated by William Duane, “The System of Discipline and manoeuvers of Infantry, “Forming the basis of Modern Tactics: Established for the National Guards and Armies of France Translated for the American Military, from the edition published by authority in 1805”, had great influence on the aspects of drill adopted by the nascent U.S. Army. And while it’s unknown whether Scott had access to them, the British had three works establishing doctrine on amphibious operations available to their officers: Thomas More Molyneaux’s “Conjunct Operations; or Expeditions that have been Carried on Jointly by the Fleet and the Army, with a Commentary on Littoral War” (London, 1759); John MacIntire’s, “A Military Treatise on the Discipline of the Marine Forces when at Sea together with short instructions for Detachments Sent to Attack on Shore” (London, 1763); and Lieutenant Terence O’Loghlen’s, “ The Marine Volunteer” (London, 1766).[4] Even if he didn’t know these works, Scott and Commodore Chauncey understood the complexity of moving 3000 men for an amphibious attack, even just a short distance. It seems most every hazard was planned for, from weather, to enemy guns, to the depth of water for Navy and Army craft approaching the enemy beach, to the time in transit.

And it was clear that Dearborn was not going to repeat the mistakes of Queenston Heights—U.S. commanders would not find themselves short of troops, or short of boats, or relying on militia to carry the day. To support the plan, the Army had been building boats for the attack for months, at Five Mile Meadow, south of Fort Niagara. Also, the Navy built shallow draft, flat-bottomed boats at Black Rock, just a few miles north of Buffalo, rowed them to Fort Schlosser, just above Niagara Falls, and portaged them to Lewiston. Two nights before the attack, troops from Fort Niagara rowed these craft under the British guns emplaced on the northern reaches of the Niagara, taking them to Four Mile Creek on Lake Ontario. As they moved down river, they came under fire of enemy artillery, and musket fire, losing two sailors.

To provide Dearborn with an overwhelming force, the Navy continued to move troops from Sacketts Harbor to Four Mile Creek, and dedicated ships to providing the landing force with naval gun fire. Chauncey’s plan for gunfire support was deliberate. Commanding the flotilla from the flagship USS MADISON, Chauncey performed a reconnaissance the night before, taking soundings off the landing beach, and placing buoys where he wanted his ships’ guns firing from. USS JULIA and USS GROWLER would place themselves in the mouth of the river, firing on batteries near the lighthouse. USS ONTARIO would place itself due north of the light house, providing crossing fire with JULIA AND GROWLER. USS GOVERNOR TOMPKINS and USS CONQUEST would provide protection on the western flank, placing themselves offshore at Two Mile Creek. USS HAMILTON, USS ASP, and USS SCOURGE would provide overhead fire for the soldiers crossing the landing beach:

“directed to anchor close to the Shore and cover the landing of the Troops, and to scour the Woods and plain whenever the Enemy made his appearance…”

- Letter from Commodore Isaac Chauncey to Secretary of the Navy Jones, No. 29. U.S. Ship Madison Niagara River. 28th. May 1813

Scott and Chauncey established a Landing Plan that would assure a quick buildup of power ashore. All available ships carried soldiers and artillery pieces for the assault, including Chauncey’s USS MADISON, USS ONEIDA, AND USS LADY OF THE LAKE. All ships that could, towed flat-bottomed boats loaded with designated landing waves. In the vanguard were Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott, commanding the overall operation ashore, and the Advanced Party of Light Troops, roughly 800 men. Following Scott and landing abreast across the beach were Brigadier General John P. Boyd’s 1st Brigade(1115 men)—Composed of the 6th Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel James Miller) planned to land on the right (western) edge of the landing beach; the 15th Regiment (Major William King) who planned to land on the center of the beach with four supporting artillery pieces and the 16th Regiment (Colonel Cromwell Pearce) who planned to occupy the left (eastern) portion of the landing beach, also with four artillery pieces. Colonel Francis McClure’s Volunteers would follow in trace.

Once the first brigade was ashore, they would be joined by the Artillery under Colonel Moses Porter, Brigadier General William H. Winder’s 2nd Brigade (1000 men), and Brigadier General John Chandler’s 3rd Brigade(1790 men). Should the situation merit further boots on the ground, Chauncey had 400 sailors aboard ship ready to land, along with the Marines of the ships’ companies.

The Navy worked with Dearborn and Scott to develop a movement plan for this considerable force, from staging and embarkation at Four Mile Creek to the beach above Newark (Niagara on the Lake) and Fort George. The sequence in which ships and towed craft moved would allow for the landing force to use prevailing easterly winds, and once arrived at the landing area, essentially execute a left flank, and pull for the beaches.

Unlike the disaster at Queenston the previous October, U.S. commanders were not going to accept any disorganization in launching the attack.

“The commanding officers of the regiments will be responsible that their boats are in perfect readiness to receive the troops.”

- - John P. Boyd, Brig.Gen., Com’d’g 1st Brigade. May 26, 1813. Four Mile Creek

Unlike at the Queenston attack, the U.S. forces prepared assiduously for the attack at Fort George. Lieutenant Colonel Scott arranged for drill and rehearsals with his second in command, Lieutenant Colonel Feeley, commanding officer of the Fort Niagara garrison, in the days prior to embarkation.[5] The day before the landings, U.S. artillery based at Fort Niagara and along the river opened fire on Fort George using hot-shot—hot-shot is cannon balls heated in an oven, producing an incendiary effect when it hits wooden structures, such as the block houses and revetments of Fort George. Additionally, Commodore Chauncey conducted a reconnaissance of current planners would term “the Transport Area”, and “Fire Support Areas”. His sailors placed buoys for gunships to reference, and he designated targets for his ship commanders.[6]

To distract the British on the morning of the 27th, Dragoons from Fort Niagara planned to move south along the river, and cross the river north of Lewiston, in plain view of the British. This would fix British defenders on the river, and if expeditiously executed, would cut-off any British forces retreating from Fort George to the south. Dearborn and his command were most likely hoping for early morning fog on Lake Ontario to mask the sound and sight of American boats moving from Four Mile Creek to a point north of the town of Newark.

Commodore Chauncey’s orders were clear on where boat captains and field commanders should be looking during transit to the landing area; the flagship would have a visible “green bough” denoting it, and each of the regimental commanders would be flying their unit colors to keep boats organized. Standard to the time, fifes and drums would announce unit movements, and with bosun’s pipes, drums, and voice commands providing direction for ships’ crews. Pre-embarkation orders included:

“Each man will take his blanket and one day’s rations ready cooked.”

- E. Beebe Asst. Adj. Gen. (Boyd, General John P. “Documents and Facts relative to Military events during the late war, p.13)

Learning from the failures at Queenston Heights, and building upon the successes at York, the combined efforts of General Dearborn and Commodore Chauncey, the respective heads of the Army and the Navy in the theater, resulted in the synthesis of a sound plan for taking Fort George, with an appropriate number of boats and soldiers on hand to execute the plan. Unlike the accounts of the crossing at Queenston, and the battle on shore, the landing at Fort George, and the seizure of the fort itself are relatively straight forward.

As per orders, reveille was at 0300, breakfast at 0330, and soldiers boarded landing boats at 0400. The fleet made way, under cover of night and a fog common on Lake Ontario given the time of year. The flotilla proceeded to assembly areas denoted by landmarks ashore, and buoys placed during Chauncey’s reconnaissance.

British forces ashore were arrayed in three distinct orientations. A third was placed to the west of the fort, a third surrounded the mostly destroyed fort, and the last third faced Fort Niagara and the river. Brigadier General John Vincent commanded 1134 men in the face of Dearborn’s 4500. The 8th and 49th Regiments of Foot, Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles, Royal Newfoundland Regiment of Fencibles, Upper Canada Militia, Captain Robert Runchey’s Company of Coloured Men, Royal Artillery, Provincial Corps of Artificers, and Grand River Native Warriors composed his force.

Vincent first noticed Chauncey’s flotilla as it emerged from the fog; when he saw Scott’s Advanced Guard pulling for the landing beach he diverted his troops from Newark to face the Americans. To protect the landing force, Chauncey’s gunboats opened up on their pre-planned targets, destroying the gun emplacements near the fort and the lighthouse in short order, and harassing troops above the beach.

The landing beach was at the base of ten-foot embankment. After gathering his force, Winfield Scott led his men up the embankment into the fire of British soldiers. It’s reported that Scott avoided a British bayonet at the crest, and lost his footing, falling backwards to the beach. Dearborn, too ill to take part in the landing itself, watched this event from aboard ship, and thought Scott was felled by a musket ball. Boyd’s 1st Brigade landed at nearly the same time, crowding the beach, and causing some issues in unit cohesion. As naval gunfire continued to pound the British onshore, Scott dusted himself off, took charge of his force again, and headed over the top. Reinforced by Boyd’s troops, the Americans drove the British back.[7]

General Vincent, reacting to the British retrograde from the beach to the outskirts of Newark, and reports that Dragoons from Fort Niagara were putting themselves in place to cross the river and cut off any British retreat from Fort George, elected to abandon Newark and the fort. Acknowledging that he was greatly outnumbered by the landing force, he sent dispatches to his units on the river and at Fort Erie, across from Buffalo and Blackrock, ordering a withdrawal to Burlington Heights. Vincent’s action sought to pluck what should have been a total victory from the grasp of the American Army.

As Scott and his men approached the fort, charges laid by the British ignited one of the magazines, with expected results. Falling debris knocked him from his emancipated horse, and breaking his collarbone. U.S. troops entered the fort, cutting the fuses of charges laid in remaining magazines. Intent on capturing the British flag flying over the fort, Scott reportedly chopped the flagpole down.

Seeing the British retreat from the area of Newark and Fort George, Winfield Scott and his Advanced Guard in full pursuit. Scott understood that the capture of the fort was only part of the key to securing control of the peninsula. Destruction or capture of Vincent’s Army was essential to further success, and Scott crafted his own orders to be flexible beyond the basic mission objectives. However, more timid souls intervened, ordering Scott to end his actions, and consolidate in a defense of captured territory. General Dearborn, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, was too ill to join forces ashore, and his appointed field commander, the politically connected Major General Morgan Lewis, chose discretion over valor, electing to sit on the gains of the morning.

By noon, the U.S. flag was flying over Fort George.

Conclusions:

No plan survives the first contact. The amphibious attack on Fort George was not a flawless operation. Despite assiduous planning, units and boats did get mixed up in the process of loading and sailing. The diversion force of Dragoons on the river failed to move quickly enough to cross the river and cut off the retreating British forces. Nobody planned for the speedy success to the extent experienced in taking the fort. Winfield Scott was held back in his pursuit of the British, allowing the majority of them to escape to fight another day.

But an amphibious assault is difficult to execute competently even by established armies. That the U.S. Army was able to accomplish a successful amphibious attack in the spring of 1813, less than a year after the declaration of war, is a credit to the professionalism of the cadre of company, field, and general grade officers that entered the war of 1812 on the U.S. side.

In 1813, the Army mostly overcame the lack of leadership experienced at the unit level in the fall of 1812. As regular troops displaced militia, and professional officers displaced political appointees, the Army found its footing against the British, continuing into 1814. Beyond having some political appointees in its officer ranks, the regulars fought under the discipline outlined by doctrinal publications and perfected through rote repetition. Officers such as Winfield Scott expressed a belief in doctrine before the word was coined, and enjoyed success in the field as a result.

And while it’s easy to grant Winfield Scott credit for exemplary leadership in preparing the Advanced Guard for battle, and in the leading them in the fight, he had only been at Fort Niagara for a short period before the attack on Fort George kicked off. The limited staffs of Dearborn and Chauncey managed to put together a plan to move an overwhelming force to the landing beach west of Fort George efficiently and effectively, counter British defenses, and transition to a ground operation quickly due to planning, organization, and drill.

But as much as we can make of the increased professionalism of the Army between 1812 and 1813, the major difference between the debacle at Queenston Heights and the victory at Fort George may have been the involvement of the U.S. Navy. At Queenston the Army failed to provide the number of boats needed for an overwhelming force to cross the river and sustain that force as British reinforcements arrived. And while the Navy wasn’t responsible for building all the boats for the Fort George battle, it did ensure that the small craft arrived at the beach in the numbers needed to provide an overwhelming force.

Fort George did not turn out to be a pivotal battle of the War of 1812. Failing to pursue and destroy the British Army doomed the U.S. to repeat battles, and the inevitable risk of facing an Army blooded fighting the French across Europe. Dearborn’s Northern Army repeatedly failed in the battles for the Niagara Frontier by robbing itself of troops in the fall of 1813, leaving militia and scant regulars to defend at Fort George, and Fort Niagara, heading into winter. Because the Army could not win successive decisive victories on the Niagara peninsula, the War of 1812 would eventually end in a stalemate in New York and Upper Canada.

Despite these long-term failures, the amphibious assault on Fort George in the spring of 1813 proved to be a singular success. The United States Army, and United States Navy, accomplished the most complex of military maneuvers at the limits of civilization in short order on one morning in May.

In gratitude: To Jere Brubaker at Old Fort Niagara for opening the archives up to me on two occasions. His knowledge of all aspects of the history of the Fort, and the area is astonishing. Thank you for your time and subject knowledge, sir.

Sources:

- Lossing, Benson J.. The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper&Brothers, New York. 1868.

- Latimer, Jon. 1812 – War with America. Harvard University Press. Cambridge. 2007.

- Barbuto, Richard V. New York’s War of 1812 – Politics, Society, and Combat. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman. 2021.

- Barbuto, Richard V. Long Range Guns, Close Quarter Combat: The Third United States Artillery Regiment in the War of 1812. Old Fort Niagara Association. Youngstown. 2010.

- Johnson, Timothy D. Winfield Scott – The Quest for Military Glory. University Press of Kansas.Lawrence. 1998.

- Dudley, William S. ed. The Naval War of 1812 – A Documentary History, Volume II – 1813. Naval Historical Center. Washington, D.C. 1992.

- Babcock, Louis L. The War of 1812 on the Niagara Frontier. Buffalo Historical Society. Buffalo. 1927.

- Barbuto, Richard V. Staff Ride Handbook for the Niagara Campaign, 1812-1814, War of 1812. Old Fort Niagara Association. Youngstown. 2016.

- New York State Historical Association Vol. XXV Quarterly Journal, Vol. VIII, 1927.

- Brubaker, Jerome. ed. Journal of Lt. Dol. George McFeeley, October 5, 1812 to about August 28, 1814. Old Fort Niagara Archives.

- Garrison Orders and Proceedings of Fort Niagara, etc. 1812-1813. Old Fort Niagara Archives.

- Cruikshank, E. ed. The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in the Year 1813. Part II. (1813). Lundy’s Lane Historical Society. Tribune. Welland. Cruikshank, E. ed. The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in the Year 1813. Part V. (1813). Lundy’s Lane Historical Society. Tribune. Welland.

- Severance, Frank H. ed. Publications of the Buffalo Historical Society Volume XVII. Buffalo Historical Society. Buffalo. 1913.

- JOINT PUBLICATION 3-02, AMPHIBIOUS OPERATIONS, 18 JULY 2014. Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff.

[1] Wikipedia, The Battle of Queenston Heights.

[2] p.18, Johnson, Timothy D. “Winfield Scott – The Quest for Military Glory” University Press of Kansas, 1998.

[3] Kretchick, Walter E. “U.S. Army Doctrine: from the American Revolution to the War on Terror”. University Press of Kansas, 2011.)(Kindle Edition, p.39

[4] Colonel Brooke Nihart, USMC, “Amphibious Operations in Colonial North America” published in “Assault from the Sea – Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare”, LtCol Merrill L. Bartlett, USMC, ed.

[5] Brubaker, Jerome. ed. Journal of Lt. Dol. George McFeeley, October 5, 1812 to about August 28, 1814. Old Fort Niagara Archives.

[6] Chauncey letter to the Secretary of the Navy 28 May 1813) Chauncey’s orders were explicit in the fields of fire for the gunboats.

[7] Barbuto, Richard V. Staff Ride Handbook for the Niagara Campaigns, 1812-1814, War of 1812. Fort Niagara Edition. Old Fort Niagara Association, Fort Niagara National Historic Landmark, Youngstown, New York. 2016

Comments

Post a Comment